HISTORY OF THE GREEN

_____________

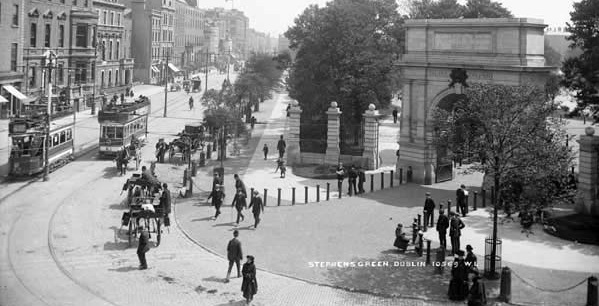

Use the image slider below to see what Stephen’s Green was once like

St. Stephen’s Green holds a very special place in the heart of all Dubliners and visitors to the city alike. A beautiful idyll in the centre of a vibrant and youthful city, the Green, as it is commonly known, is the perfect sanctuary for shoppers, office workers and tourists searching for that well-earned rest from the hustle and bustle that is Dublin life. However, it wasn’t always the city centre paradise it has turned out to be. Until 1663, St. Stephen’s Green was a marshy common on the edge of city, used for the grazing of sheep and cattle, public executions and witch burnings. In 1664, Dublin Corporation, seeing an opportunity to raise much needed revenue, decided to enclose the centre of the common and sell land around the perimeter for building. Buildings soon sprung up around the lime tree enclosed common, and St. Stephen’s Green was born. However, at this time, the park was only accessible to those who owned plots around the park and it wasn’t until over 200 years later that the hoi-polloi of Dublin’s fair city managed to get through its front gates. Up until it was opened to the public, the Green underwent many changes. The housing that originally surrounded the park was replaced by magnificent Georgian townhouses, and those with slightly deeper pockets replaced the former residents.

Famous and infamous residents of the area around St. Stephen’s Green included Thomas ‘Buck’ Whaley, Arthur Wellesley, John Philpot Curran, and ‘Copper Faced’ Jack Scott. In 1814, control of the St. Stephen’s Green Park passed over to the Commissioners for the local householders, who redesigned its layout and replaced the walls with railings. After the death of Prince Albert in 1861, Queen Victoria suggested that the park be renamed Albert Green and have a statue of Albert at its centre-a suggestion roundly rejected by Dublin Corporation and the people of the city, much to the chagrin of Victoria. William Sheppard designed the current landscape of the park and, thanks to the largesse of Sir A.E. Guinness; St. Stephen’s Green was officially opened to the public on Tuesday, 27 July 1880. By way of thanks, the city commissioned a statue of Guinness, and he can now be seen facing the Royal College of Surgeons on the Green’s west side.

Like the city where it is located, St. Stephen’s Green Park has played witness to many of the turbulent episodes of Irish history, with the most famous being role it played in the 1916 Easter Rising. During the Rebellion, a group of insurgents, under the command of Michael Mallin, and his second in command Constance Markievicz, established a position in St. Stephen’s Green. They confiscated vehicles to establish road blocks on the streets that surround the park, and dug defensive positions in the park itself. This proved unwise when elements of the British army took up positions in the Shelbourne Hotel and from where they could shoot down into the entrenchments. The rebels, finding themselves in this precarious position, withdrew to the Royal College of Surgeons on the west side of the Green to carry on the fight but, nevertheless, the rising ultimately failed. In one famous incident, gun fire was temporarily halted to allow the ground’s man feed the local ducks.

Today, the park is often informally called Stephen’s Green and, at 22 acres, it is the largest of the parks in Dublin’s main Georgian garden squares. Much of the present day landscape of the square that surrounds the park comprises many modern buildings, some in replica Georgian style, and little survives from the 17th and 18th centuries. The park itself is now operated by the Office of Public works and features much that is interesting to the visitor. One of the more unusual aspects of the park lies on the north-west corner of the central area-a garden for the blind with scented plants that withstand handling and are labelled in Braille. To the south side of the main garden lies a bandstand, which is often frequented by students, workers and shoppers on Dublin’s sunnier days. Other notable features well worth a visit are:

- The Fusiliers’ Arch at the Grafton Street corner, which commemorates those of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers who died during the Second Boer War.

- A sculpture representing the Three Fates inside the Leeson Street gate, which was gifted to the Irish people by Germany in thanks for help to German refugees after World War II.

- The WB Yeats Memorial garden with a sculpture by Henry Moore.

- A bust of James Joyce facing his former university at Newman House.

- A memorial to the Fenian leader Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa near the Grafton Street entrance.

- A bronze statue at the Merrion row corner of Theobald Wolfe Tone, the leader of the 1798 rebellion.

- A memorial to the Great Famine of 1845-1850 by Edward Delaney.

- A bust of Constance Markievicz on the south of the central garden.

- A statue of Robert Emmet standing opposite his birthplace at no. 124.

- A memorial of Thomas Kettle, war poet, nationalist and fatality of the Great War.

- A bust of James Clarence Mangan, Irish literary figure.